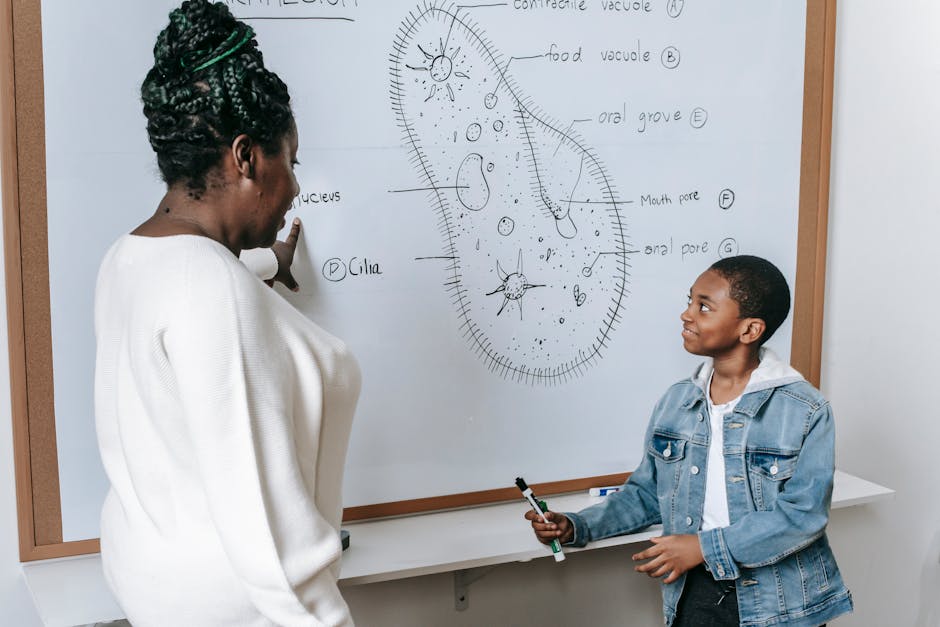

Creating engaging lessons that use real-world problems as frameworks is one of the most effective ways to teach students. In fact, studies show that this approach is more efficient than teaching under the traditional framework of telling students what knowledge they should have and testing them on it!

By creating lessons framed by a problem or question derived from the real world, teachers can easily connect with their students' interests and needs. Claim evidence responses ask students to analyze whether an assertion or hypothesis is true by looking at the claims made along with any supporting facts or arguments. These answers can be drawn out via brainstorming, writing, or speech. Students must consider both validity and reliability of these sources when determining if the argument has strong backing.

Types of Claim Evidence

The next step is to determine what kind of claim evidence you have for or against your topic. There are five main types of claim evidence, with the appropriate level of strength depending on the subject matter.

The first type of claim evidence is called "supporting anecdote." These are stories that illustrate how well-intentioned actions led to positive results. For example, a story about a student who was distracted by bad behavior during class would be an example of supporting anecdote.

A second type of claim evidence is called "case study." This is an extended example of something happening once. A case study could look at two different courses and compare their effects on students.

Third, there is "experiment." An experiment tests whether or not one theory is more likely than another. For instance, testing whether teaching science as a process rather than concept will help students learn more quickly may lead to improved test scores.

Fourth, there is "proof based on mathematics, logic, physics, or psychology." Using math to prove theories such as evolution is common. Physics can show that natural laws exist and apply to certain situations, and psychologists use research to validate theories.

And lastly, there is "scientific consensus." As mentioned before, this term refers to where most scientists agree on some fact. For example, the majority of experts believe that eating meat contributes to environmental problems.

Applying Claim Evidence

The next step is applying this approach to your teaching and learning. Depending on the topic, setting up a claim test or using an existing claim test can be done immediately.

For example, if you wanted to teach about how plants need sunlight to grow, then using the analogy of food cannot work because it does not require light. Using the claim test for evidence could prove tricky as there are many factors that influence whether or not plants require light for growth.

That being said, some plants will continue to grow even when no direct light source is present so we may still use the analogy of food and sunshine to explain plant growth.

When applied to other topics, making references to the claim test is easy! Simply search through your sources and determine whether or not the concept requires the claimed element.

Understanding Counterarguments

A strong argument includes evidence that supports your claim, as well as a good rebuttal of the claims of your opponent. The latter is known as a counterargument or a response argument.

In science education, one of the key components of reasoning or logic is using evidence to prove your claim. This can be done through describing how and where you found an element, determining the ratio of this element to other elements, or testing your sample to see if there is more or less of it than expected.

When teaching students about evolution, for example, they must make logical points based on the theory and disprove any theories such as creationism. Similarly, when teaching about climate change, students have to consider whether or not man-made changes are causing global warming.

These types of arguments require careful planning . You will want to make sure you have enough information to back up your claims and potential objections. These could include looking up studies, talking to people around you, and finding sources via research methods .

There are two main reasons why someone may dispute your claim. First, they may question if your source material is reliable. Second, even if your source materials are sound, they may doubt the accuracy of your conclusions.

Identify the source

Source identification is one of the most important steps in using CER effectively. You will want to make sure you know who wrote down what before applying anything to real life scenarios!

In your science lesson, you may be asked to use an assertion with supporting evidence. Using claim response can help you do this more efficiently by providing you with a tool to use.

By practicing using CLAIM EVIDENCE RESPONSE in lessons, you will become more efficient at it. This way you will not have to spend too much time finding the sources for each claim!

You can also use CLAIM EVIDENCE RESPONSES as a starting point to create your own argument or rebuttal.

Look for an ambiguity

In science, when you find yourself struggling to determine the best theory, method, or process of something, there is usually one thing standing in your way.

It's called the "paradox of confirmation." This term comes from psychology and refers to the fact that even though most people agree that theories which describe reality as being completely solid are appealing, true believers will often reject the theory because it makes them feel bad.

When this happens, they use reasoning like : "The theory cannot be correct, because if it was then I would agree with it!"

By arguing against their own beliefs, they create a situation where they have to defend themselves by proving the theory wrong. It puts more pressure on them to prove that theory wrong than proof that it is right.

This is why sometimes people who believe in relativity struggle with quantum physics. Or someone who believes in evolution may argue against big-cat conservationists and vice versa.

It is important to remember that while these opposing theories may both sound silly at first, they must both be given serious consideration before we can say definitively what happened out there.